One big issue that had been bugging me for a long time is that of the radio equipment. The Boeing 247, and especially that later “D” variant utilized cutting edge technologies, which included some state-of-the-art radio equipment. The problem is, that by today’s standard, and thus the standard of Microsoft Flight Simulator, those technologies are hopelessly outdated and simply not used anymore.

This bears some issues for us. Since we want to bring you a most realistic and historically accurate experience, the lack of low-frequency radio stations and the modern VHF communication, takes away from this experience.

My original idea was to cheat, by modelling a vintage radio but have it use the modern frequency range. I even thought you could use the same equipment to pick up the Morse code of the VOR stations as an added bonus.

Then I met celestial navigation and radio expert Eric van der Veen. He released a stand-alone module for MSFS last year, which adds radio range stations to the sim. We started talking, and he since wrote a wasm module exclusively for the Wing42 Boeing 247D that integrates his work directly into the aircraft. And if you have no idea what “radio range navigation” is, allow me to blow your mind!

Some history

In the 1930s, wireless technology was still fairly new and the frequencies used were limited to around 150 kHz (then called “kilocycles”) to around 15 MHz. Communication would sometimes still take place using Morse-code, rather than radio-telephony. When it comes to radio navigation, direction finding became more advanced, so pilots could find out the bearing to a radio transmitter – similar to modern ADF navigation.

But engineers also worked on ways to figure out on what radial of the radio station an aircraft was. Nowadays, we have VOR stations and NAV instruments, which provide that information. The Radio Range Stations of the 1930s were the predecessor of this technology.

Radio Range Navigation

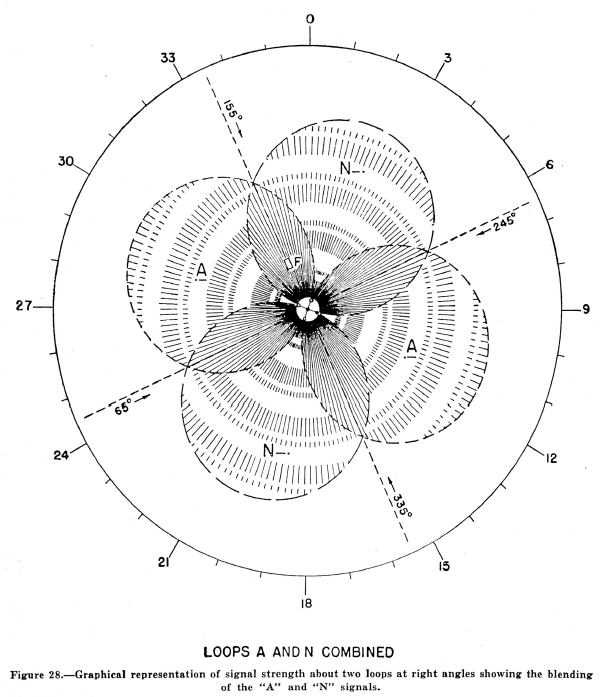

The ground stations for the radio range consisted of two antennas, laid out perpendicular to each other. One transmitter was used for both antennas, but a mechanical timing mechanism switched between them. The timing mechanism thus encoded CW Morse code on the signal of the two antennas with one signal being the inverse of the other.

The signals encoded were “A” (· ‒) and “N” (‒ ·). In the area between the two antennas, the signals would overlap and create a constant output. This area would be called “the beam” and the antennas would be oriented in a way that these beams formed airways between the stations. Furthermore, the power output of the antennas was varied to bend the beam, allowing for non-perpendicular airways.

But how do you actually use this in practice? The interesting thing about radio range navigation is that there’s no instruments involved – at least not in the 30s and 40s. Instead, the pilots tuned in to the radio station and LISTENED to the transmission. Radio Range Navigation was literally “flying by ear” and we are bringing it to MSFS!

It will be one of the most challenging and definitely the most annoying method of aerial navigation you’d ever tried. It is a real challenge listening to Morse code for hours, trying to differentiate between an “A” and an “N” to get your bearings right. But you will feel a great sense of accomplishment when you finally landed at your destination.

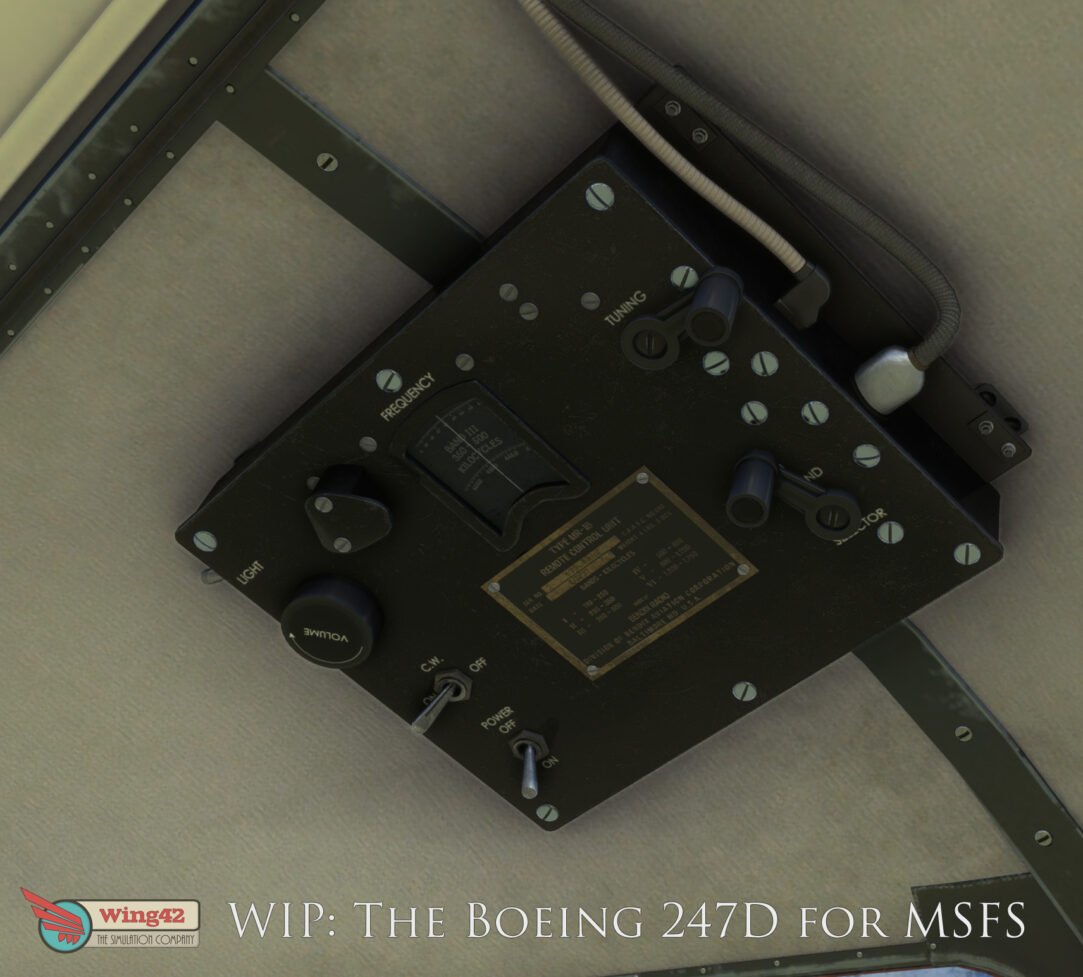

The original MR-1B (and similar models), covered a frequency range of 150 to 15000 kHz (formerly called “Kilocycles”) in 6 bands. One of the cranks would be used to shift to the next band, while the other crank then fine-tunes to the desired frequency.

For our representation, we adjusted the frequency range slightly. By cutting off the top end, each band becomes more refined and easier to tune.

By putting the radio in the “continuous wave” mode, you will be able to pick up the Morse code of the radio range stations – provided you tuned the radio to the right frequency. Make sure to turn up the volume and listen to the transmission of the radio station. Depending on the sector you’re flying through, you will either hear “beeeeeeeep beep ….. beeeeeeeep beep …..”, or “beep beeeeeeeep ….. beep beeeeeeeep ….. “. If you’re flying “on the beam”, those two signals will overlap and so you’ll hear a constant “beeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeep” – only interrupted by a Morse-code identifier of the station, which is transmitted every minute.

You can correlate what you hear to the layout of the stations in your area of flying and by flying some radio-range standard procedure, you can even work out your precise position, relative to the station.

Final Thoughts

We only scratched the surface about this vintage way of radio navigation! During the 30s, 40s and 50s, a set of standard procedures were developed for radio ranges. With the Wing42 Boeing 247D, we will include training material from the 1940s that will teach you the more complicated maneuvers and instrument procedure as used at that time.

Time for me to finish up this add-on, eh? Back to work!

– Otmar

P.S. I recently uploaded screenshots of all liveries that will be included in our addon. Check it out:

Microsoft Flight Simulator Add-ons

Microsoft Flight Simulator Add-ons Flight Simulator X Add-ons

Flight Simulator X Add-ons

14 Replies to “Dev Blog 16 – Flying “the beam””

Ala13_Kokakolo

Hi,

I am really interested in this plane. Two questions: Will this radio system cover the whole world or just USA? Second: Will we also have the posibility of using that radio (or a modern one) to use VORs, DMEs and ADFs?

Otmar Nitsche[ Post Author ]

We have placed radio stations at historic locations all around the world. However, there’s around 400 stations in the U.S. alone and the remaining 300 are distributed in the rest of the world. So as you can imagine, the density of these navaids is much higher in the U.S.

We don’t have any equipment to pick up signals from VOR, DME or NDBs. The only frequency range that the radio could potentially pick up would be the NDBs, that still to this day transmit on roughly the same spectrum as the radio range stations. However, since we have no direction finder in the aircraft, it would be of little utility to be able to pick up NDB signals.

All of this fits the profile of the aircraft very well though, since the vast, vast majority of 247s were used by United for their coast-to-coast service in the U.S.

Patrick Buedi

Hello Otmar. Regarding the Radio Range beacons CSV file for import to Little NavMap: I created a small Icon and asked Albar if he thinks it is possible to include the Icon for those type of beacons in LNM and he immediately responded. The thread is over here: https://www.avsim.com/forums/topic/617069-new-userpoint-type-symbol-possible/?tab=comments#comment-4747030

It is not part of LNM yet of course, but in the Reply he posted, there is a link to the Icon he converted and it just needs to be put into the LNM Settings directory and voila! We have the Radio Range beacon Icon in LNM 🙂

When adjusting the name in the CSV you seem to be supplying, it will show up correctly and not as a VORTAC or TACAN like the Mod from Eric 🙂

Otmar Nitsche[ Post Author ]

That is amazing – what a wonderful idea! I passed the link on to Eric to look into. Thank you very much.

Tony Vallillo

The vast majority of all of the 247’s ever built were indeed owned by United, and interestingly that situation led directly to the development of the DC series of airliners. United was originally called Boeing Air Transport, and was a part of the Boeing empire, as it were. They thus were able to monopolize the production of the 247 and keep it out of the hands of competitors TWA and American. This, of course, put these other airlines at a competitive disadvantage, which Jack Frye of TWA was quick to rememdy – he persuaded Donald Douglas to build a better airplane, which Douglas did – initially the DC-1 and its’ production version the DC-2. C. R. Smith went farther, talking a by-then-reluctant Douglas to enlarge the DC-2, and thus was born the DST (the Douglas Sleeper Transport, or in its’ day version the DC-3). United now was in the competitive corner that they had contrived to put TWA and American into, and had to order the DC’s as quickly as they could get rid of the 247’s, which went used to smaller airlines like PCA.

Andre92

Hello Otmar,

great update and really like the detail put into this radio system. For me personally, flying these vintage aircraft is all about handling the engines. Having to take care of them is a big part of the experience (at least for me). This is what sets apart the PMDG DC-6 from all the other vintage plane addons available currently. Do you have any plans in the same direction?

Good luck with this great project!

Otmar Nitsche[ Post Author ]

Oh for sure! If time permits it, I’ll write another blog post about it! 🙂

UnsealedKarma

Very interesting. I recently read the memoirs of SAS Captain Rønhof. He describes a nighttime approach to Aalborg in a DC-3 in the late 1940s. As the first officer he witnessed the captain trying to ride the beam, but according to Rønhof, he didn’t understand the system and searched for beeps rather than the constant tone. However Rønhof was there to save the day and plane.

Otmar Nitsche[ Post Author ]

That’s interesting, and it goes with our findings too. It is easy to get disoriented with this system – you turn left when you should turn right, or something similar happens very quickly. I can also imagine that if you have a high work load and come to the point of sensory overload, you could easily make mistakes like that.

Something else that came to my mind: The U.S. actually had some mid-air collisions, when two aircraft flew the beam in opposite directions. It became a good practice to fly slightly right off the beam. You can do this in the sim too – by flying a heading that is not a constant beep, but where parts of it are a bit softer than the other.

Tony Vallillo

Actually, that might not have been as erroneous as it seems. According to Ernest K. Gann, in his magnificent memoir “Fate is the Hunter”, most pilots in that era did not fly in the center of the beam, which might have been more than a mile wide some distance from the station. Instead, they held to one side, where they got one letter stronger than the other, but still merged into a sort of hum with a bit of an A or N superimposed.

In any event, the Bible of instrument flying in that era was Assen Jordanoff’s “Through the Overcast”. One can probably still find this on Ebay.

Odd "Elvis" Goderstad

I am sooo looking forward to this 🙂 Now if someone could start to make detailed airports, as they were in the 30’s….

Tony Vallillo

It looks like the people behind the Red Wings Constellation are working on some 1930’s scenery for areas in the USA and Europe. This is an exciting development, the more so since at this point the only vintage scenery that I am aware of is from Cal Classic for FS9!

Artur

Dear Otmar, would that be a profanation if u add NDB gauge as an option, for those who do not fly US, or find sound nav as too disturbing?

Otmar Nitsche[ Post Author ]

One big issue I had when designing the instrument panel, was to find the space for some of the stuff we really need. There’s simply no space on the panel for another steam-gauge. The advantage of Radio Range Navigation is that it doesn’t require an instrument, since it is flown by ear.